Curry County, New Mexico “House of Horrors”: Texico Child Abuse Case Exposes CYFD Failures and the Dark Reality of Foster Care Safety

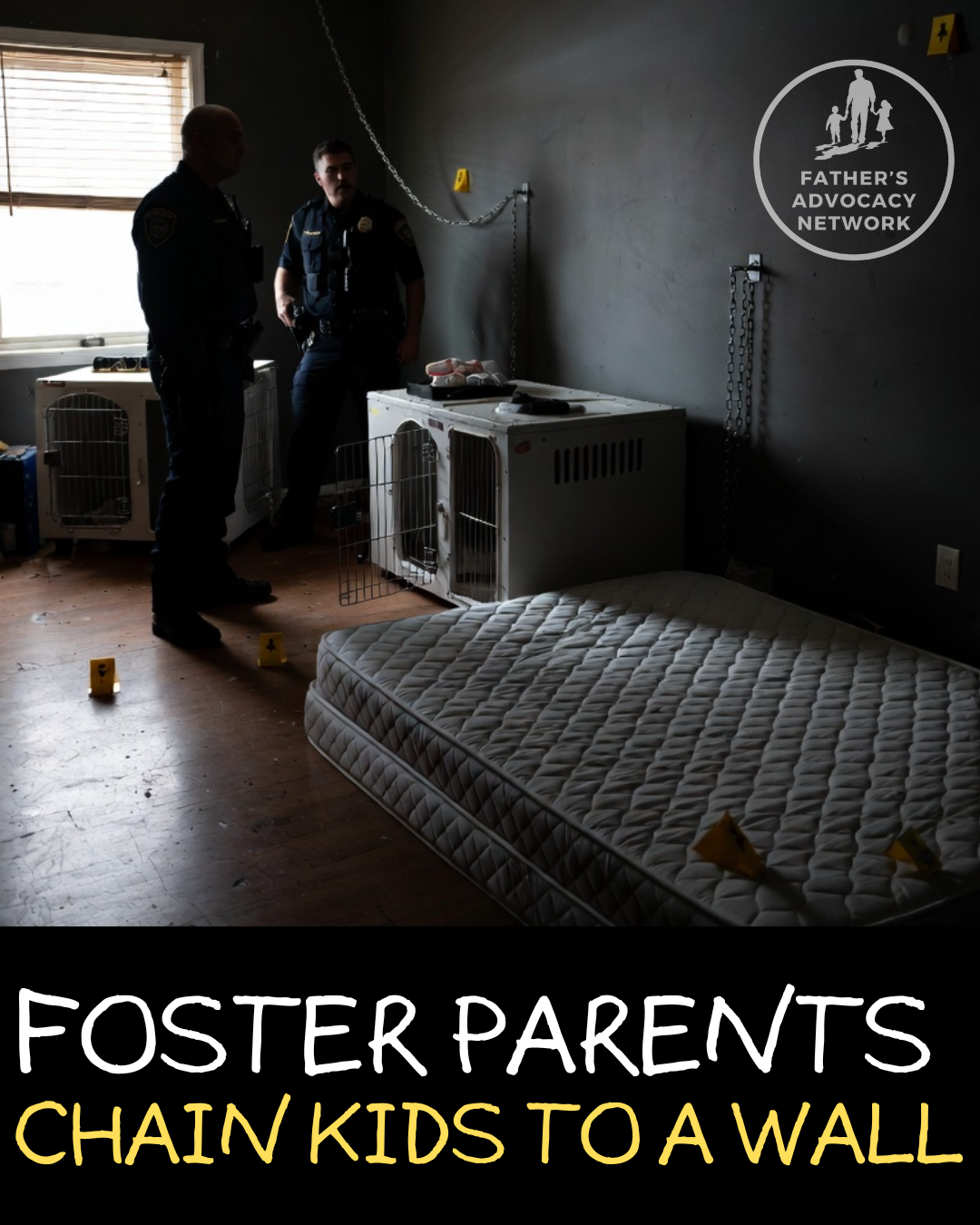

CURRY COUNTY, NEW MEXICO — In Texico, just outside Clovis, New Mexico State Police executed a search warrant that revealed what prosecutors later described as one of the most cruel and disturbing child abuse cases they had ever seen.

Children chained to beds.

Children locked in cages.

Children starved.

Security cameras capturing it all.

The case, prosecuted by the Ninth Judicial District Attorney’s Office, involved Jayme (Lynne) Kushman, Jaime (Kay) Sena, and Lora Melancon, and led to guilty pleas and prison sentences after investigators recovered three days of video evidence showing prolonged abuse.

But this is not just a Texico crime story.

This is a Curry County child welfare failure story — and a case study in how the foster care and child protection system often works only after catastrophic harm has already occurred.

What New Mexico State Police Found in Texico, Curry County

After receiving a tip in July 2022, New Mexico State Police (NMSP) and New Mexico CYFD (Children, Youth & Families Department) executed search warrants at a residence in Texico.

According to prosecutors:

Six children were living in unsanitary conditions

Security footage showed children allegedly chained for long periods

One child was allegedly chained to a bed for 14 consecutive hours without food, water, or bathroom access

Prosecutors described scenes of starvation and physical abus

A judge later classified the crimes as Serious Violent Offenses, underscoring the severity.

The evidence was so strong that guilty pleas followed.

But here is the uncomfortable question:

Where was the system before the raid?

Foster Care Safety Myth vs. Foster Care Reality

While this case involved a household with multiple children — including at least one foster child — it highlights a broader truth that child welfare agencies rarely discuss publicly:

Children in foster care are statistically 2 to 10 times more likely to be sexually abused than children living with their biological families.

That range comes from analyses of federal and state data, including research summarized by the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform (NCCPR) and state-level audits.

Even more troubling:

Multiple studies show children in foster placements face elevated risks of severe injury and fatality compared to similarly situated children in intact families.

Yet in courtrooms across America — including in New Mexico CYFD cases — removal is routinely framed as the “safer” option.

Safer than what?

Most Children Are Not Removed for Abuse — But for “Neglect”

Nationally, the majority of children are removed from their homes for “neglect.”

Not sexual abuse.

Not torture.

Not chaining.

Neglect.

And “neglect” is one of the most loosely defined terms in child welfare law. It often includes:

Poverty

Inadequate housing

Lack of childcare

Utility shutoffs

Missed medical appointments

Subjective judgments about supervision

In practice, neglect frequently becomes a label for poverty plus personal interpretation by a caseworker.

Which means removal decisions often hinge on discretion.

If the same standards applied globally — in communities where children share beds, walk long distances, lack indoor plumbing, or live in crowded homes — millions of children worldwide would qualify for removal under U.S.-style neglect statutes.

That’s not an exaggeration.

It’s a reflection of how broad the definition has become.

The Trauma of Removal Is Not Neutral

What’s rarely told to judges or families:

Family separation is itself traumatic.

Peer-reviewed research has shown removal can cause:

Attachment disruption

Increased anxiety and depression

Elevated risk of behavioral problems

Higher rates of future justice system involvement

Greater vulnerability to exploitation

Children placed into foster care do not enter a neutral environment.

They enter:

New authority structures

New adults with power over them

Often multiple placements

Sometimes institutions

And when oversight fails — as it did in Curry County — the consequences are devastating.

Oversight Failure in Curry County and Beyond

The Texico case required:

A tip

A search warrant

New Mexico State Police

Seizure of video evidence

It did not originate from routine monitoring.

That raises hard questions for New Mexico CYFD oversight procedures:

Were regular home visits conducted?

Were children interviewed privately?

Were warning signs dismissed?

Were prior complaints investigated thoroughly?

These are not anti-police questions.

They are pro-child questions.

The Larger Pattern: When the System Assumes It Is Safer

The most dangerous myth in child welfare is that state custody equals safety.

It does not.

Removal is a high-risk intervention.

When agencies remove children — especially for neglect — they assume responsibility for every harm that follows.

And data repeatedly shows:

Foster care is not inherently safer.

In many measurable categories, it is riskier.

The Texico “Dungeon” and What It Reveals

Video evidence in the Curry County case reportedly showed children chained, punished with restraints, and treated in ways prosecutors described as cruel and inhumane.

The existence of cameras inside the home — capturing abuse — is particularly chilling.

It suggests confidence.

It suggests normalization.

It suggests belief that no one would intervene.

That is not just a criminal problem.

That is a systemic blind spot problem.

Curry County, New Mexico Must Ask:

How many other homes operate below the surface?

How many removals were truly necessary?

How many families needed resources instead of separation?

How many children are currently in placements assumed safe — but not verified safe?

Conclusion: The System Cannot Claim Moral High Ground Without Accountability

The Texico child abuse case is horrifying.

But horror alone is not enough.

If the foster care and child protection system continues to:

Remove children primarily for neglect

Rely on subjective judgment

Assume oversight is functioning

Ignore data showing elevated abuse risk in foster care

Then cases like this are not anomalies.

They are predictable outcomes.

And until that is confronted honestly — in Curry County, New Mexico, and nationally — children will continue to be placed into systems that promise safety but sometimes deliver the opposite.

Federal Child Welfare Data

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS), Administration for Children & Families (ACF).

AFCARS Report (Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System).

National data showing the majority of removals are for neglect, not physical or sexual abuse.

Child Maltreatment Reports (HHS, annual).

Provides data on substantiated abuse, foster care placements, and fatality rates.

Removal for “Neglect” – Majority of Cases

HHS Child Maltreatment Report (most recent available year).

Shows approximately 60–75% of removals nationally are categorized as neglect.

Pelton, Leroy H.

The Myth of Classlessness in Child Welfare.

Research documenting how poverty is frequently conflated with neglect.

National Coalition for Child Protection Reform (NCCPR).

Analysis of neglect removals and poverty-related family separation trends.

Abuse Risk in Foster Care (2–10x Risk Range)

National Coalition for Child Protection Reform (NCCPR).

Review of state and federal data suggesting children in foster care are at significantly elevated risk of sexual abuse compared to children in the general population.

Doyle, Joseph J. (MIT / University of Chicago).

Child Protection and Child Outcomes: Measuring the Effects of Foster Care.

Found children placed in foster care had worse long-term outcomes than similarly situated children left at home.

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Reports on child abuse incidents in foster care and oversight failures.

Euser, S., et al. (2013).

The prevalence of child sexual abuse in residential and foster care: A meta-analysis.

Child Abuse & Neglect Journal.

Found significantly elevated abuse risk in out-of-home placements.

Trauma of Removal & Foster Care Outcomes

Bruskas, D. (2008).

Children in foster care: A vulnerable population at risk.

Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing.

Rubin, D. M., et al. (2007).

The impact of placement stability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care.

Pediatrics Journal.

Turney, K., & Wildeman, C. (2017).

Mental and Physical Health of Children in Foster Care.

Pediatrics.

Sroufe, L. A. (2005).

Attachment research demonstrating the long-term impact of caregiver disruption.

Foster Care Fatality & Severe Harm Data

U.S. HHS Child Maltreatment Reports – Fatality Tables.

Shows children with prior CPS contact are disproportionately represented in child fatalities.

GAO Reports on Foster Care Oversight and Safety Monitoring.

Oversight & Monitoring Concerns

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office).

Multiple audits documenting inconsistencies in foster care home monitoring and state reporting systems.

State-level Inspector General audits (various states).

Findings repeatedly show screening errors, delayed response times, and improper case classification.